Teresa was driving home from university when her phone rang—one of those calls that sounds ordinary until it isn’t.

On the line was our oldest son, sounding both exhausted and frustrated.

“Mom,” he said, “how did you ever get us to go to bed on time when we were little?”

This is never a nostalgic question.

It’s a distress signal.

Recently, their four-year-old, our grandson, has been having what can only be described as epic bedtime meltdowns. Tears. Screaming. Full-body resistance. The kind of tantrum that makes you briefly wonder whether bedtime has been outlawed and you missed the memo. On a scale of one to ten, these were solid eight-point-nines—seismically significant.

Now, here’s the part that matters.

Teresa didn’t jump into problem-solving mode.

She didn’t prescribe a bedtime system.

She didn’t say, “Well, you just need to be firmer”—the kind of advice that sounds decisive but rarely helps.

Instead, she paused.

And then she asked a question that surprised even me:

“Tell me about the twelve hours before bedtime.”

That question is the gift of grandmotherhood.

When you’re a parent in the middle of it, behavior feels urgent. Personal. Loud. When you’re a grandparent, you have the luxury of altitude. You can see patterns instead of problems.

So our son began to talk.

An exhausted mom.

An overstretched dad.

Twins arriving earlier this year.

A house full of love—and upheaval—at the same time.

Nothing dramatic. Just the quiet accumulation of change.

And somewhere in that swirl, a four-year-old who feels a little lost in shuffle.

What looks like a bedtime battle starts to look more like a bidding war for connection. What sounds like defiance begins to resemble grief—grief for attention, for routine, for the world as it was before his twin brothers arrived.

Of course, when you’re four, you don’t say, “I’m struggling with the emotional displacement that often accompanies major family transitions.”

You scream.

You cry.

You resist pajamas with the passion of a constitutional lawyer.

And suddenly the question shifts from, “What’s wrong with this child?” to something far more interesting:

What if this behavior makes perfect sense—once we know the context?

Get Curious

What Teresa did in that moment was a game-changer.

She got curious.

Curious in a disciplined way. The kind of curiosity that resists the instinct to label, judge, or fix—and instead asks a better first question.

This instinct sits at the heart of the book What Happened to You?, where Dr. Bruce Perry makes a deceptively simple point: behavior makes sense when you understand what shaped the nervous system behind it.

His work reframes one of our most common reflexes. When someone melts down, lashes out, shuts down, or acts in ways that feel irrational or disruptive, we instinctively ask:

What’s wrong with you?

But Perry invites a different question:

What happened to you?

That shift—from judgment to curiosity—changes everything.

Because the moment we decide someone is “just difficult,” “too much,” “immature,” or “a problem,” we stop listening. We write them off. We escalate. Or we disengage entirely.

And in doing so, we often miss the deeper truth:

Behavior is the signal, not the source.

Our grandson’s meltdown wasn’t really about bedtime.

It was about connection.

About displacement.

About a nervous system that didn’t yet have language for loss, transition, or longing.

And here’s the uncomfortable part: this doesn’t stop at age four.

Adults have more vocabulary—but we’re not always better regulated.

The colleague who snaps in meetings.

The partner who withdraws.

The friend who suddenly becomes critical or distant.

The stranger whose anger feels wildly disproportionate.

In each case, we stand at a crossroads.

We can judge.

We can react.

We can match intensity with intensity.

Or we can do what Teresa did in that car that afternoon.

We can widen the frame.

We can ask, “What might the last twelve hours—or twelve years—have been like for this person?”

Curiosity doesn’t excuse harmful behavior.

But it does prevent us from mistaking the signal for the source.

And often, when we pause long enough to see it clearly, what looks like bad behavior is actually something else entirely:

A nervous system asking for safety.

A heart asking for reassurance.

A human being asking—clumsily, imperfectly—to be seen.

What Actually Helps—and Why it Works

Here’s the part most of us miss:

When people are overwhelmed—kids or adults—their nervous system shifts into protection mode. Fight. Flight. Freeze. In that state, the parts of the brain responsible for reflection, empathy, and problem-solving go offline. Reflexes take over.

Which means this:

Trying to reason with someone who is dysregulated usually makes things worse.

That’s why timing matters more than technique.

Perry describes a simple but powerful sequence for moments like these:

Regulate first

Calm the body before you address the behavior.

Relate second

Restore connection before you correct.

Reason last

Wait for regulation before you problem-solve.

Curiosity works not because it’s kind, but because it’s regulating. It slows the moment down long enough for the nervous system to settle, so understanding (and change) can actually happen.

And that’s where things begin to shift from reaction to response.

Here’s What That Looks Like in Real Life

1. With kids: zoom out before you clamp down

A child melts down at bedtime. Screaming. Tears. Total resistance.

The reflex is correction: “Enough. Go to bed.”

Curiosity asks a different question: “What did today take out of them?”

Daycare. A new sibling. Skipped naps. Ten small disappointments stacked together. When you start there—before discipline—you’re no longer fighting the child. You’re responding to the context.

Regulate. Relate. Then reason.

2. In marriage: don’t argue with the surface behavior

Your partner snaps over something small. Or goes quiet. Or suddenly seems miles away.

It’s tempting to respond to the behavior itself: “Why are you being so defensive?”

Curiosity sounds more like: “Something else is going on—what am I not seeing?”

Stress at work. Feeling unappreciated. Old wounds quietly activated.

This doesn’t mean ignoring the impact. It means asking a better first question—one that invites honesty instead of hardening positions.

3. At work: separate competence from capacity

A colleague misses a deadline. Gets short in meetings. Seems unusually reactive.

The easy story is character: “They’re unprofessional.”

Curiosity reframes it as capacity: “Are they overloaded? Under-supported? Dealing with something invisible?”

Leaders who pause here don’t lower standards—but they raise effectiveness. They address the real problem instead of managing symptoms.

The Shift That Changes Everything

Judgment closes the story.

Curiosity opens it.

It doesn’t excuse harmful behavior—but it keeps us from mistaking the signal for the source.

Often, what we call bad behavior is simply unmet need, unprocessed stress, or unspoken grief—leaking out sideways.

And when we learn to get curious first, we don’t just respond better.

We see people more clearly.

Until next week,

Jonathan Penner | Co-Founder & Executive Director of LifeApp

Resources To Dig Deeper

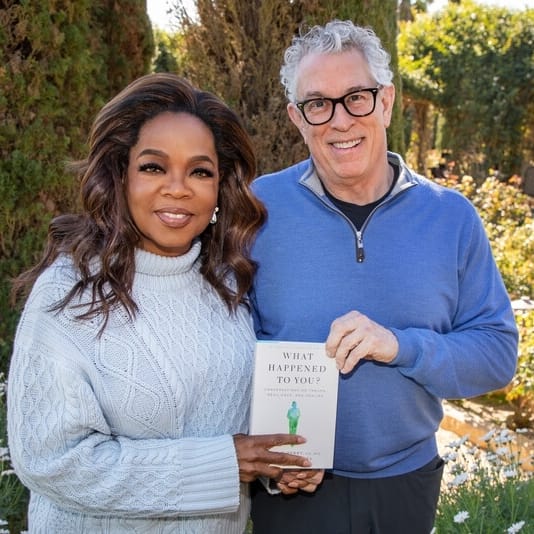

Book

What Happened to You?

This book explores how our earliest experiences quietly shape our behavior, reactions, and relationships long after we’ve grown. Rather than asking “What’s wrong with you?” the book invites a more compassionate and scientifically grounded question: “What happened to you?” Through deeply human stories and accessible neuroscience, it reframes behavior not as a personal failure but as an adaptation—opening the door to greater self-understanding, resilience, and more generous ways of relating to ourselves and others.

-Oprah Winfrey and Dr. Bruce Perry

Video

What Happened to You?

If this newsletter invited you to ask, “What happened earlier today?” this conversation with Oprah and Dr. Bruce Perry widens the lens to a lifetime—and shows you why that question changes everything. In one hour, you’ll hear a world-leading trauma psychiatrist translate decades of brain science into plain language you can actually use: why people (including us) overreact, shut down, lash out, or self-sabotage—often without understanding why—and why “what’s wrong with you?” is almost always the least helpful starting point. The payoff isn’t just insight; it’s a new way of seeing your partner, your kids, your coworkers, your parents, and your own patterns with more clarity and less shame—so you can respond with steadiness instead of reflex, and compassion without excusing harm.

-Dr. Bruce Perry with Oprah Winfrey on Super Soul Sunday (41:22)

Music

This Is Me Trying

In “this is me trying,” Taylor Swift gives voice to what so often sits beneath so-called “bad behavior”: shame, regret, fear, and the fragile courage it takes to keep showing up anyway. The song traces a person who looks stalled, inconsistent, or self-sabotaging from the outside—but from the inside is working desperately to stay afloat. What sounds like withdrawal, defensiveness, or failure is revealed as effort under strain. The lyrics invite us to pause our judgments and listen more carefully, to recognize that progress doesn’t always look impressive, and that sometimes the most meaningful act is simply not giving up. In that way, the song echoes this newsletter’s central insight: before we label behavior as a problem, we might first ask what kind of trying it represents.

-Taylor Swift (3:15)